We have analysed that the modelling process from the Draft Limerick Shannon Metropolitan Area Transport Strategy (LSMATS) and in this article, we lay out our specific concerns with this process. We have concluded that this modelling process is deficient in a number of respects, and not reliable for predicting the future of the Limerick region transport mix.

LSMATS proposes “strategy outcomes” including modal share of transport modes based on “a strategic modelling process” (PDF: Public Consultation Document and consultation site).

We, The Limerick Cycling Campaign, recommend:

- That the Minister for Communications, Climate Action and Environment and Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport immediately pause the consultation process and review LSMATS to overhaul it into a fresh strategy that provides ambitious and necessary targets for a transformed mobility strategy, and a viable, liveable future Limerick.

- The immediate funding and implementation of the proposed and agreed primary and secondary cycle networks as identified in the Limerick Metropolitan Cycle Network Study (Arup, 2015) and referenced in the Draft Strategy.

What is a “modelling process”?

The National Transport Authority constructed a “demand forecasting model” (PDF: Road model development report).

The designer of a model attempts to account for relevant real-world data. In this case, it covers demand for transport such as driving, walking, cycling and public transport. A model can be used to attempt to predict future transport behaviours.

Models must be “calibrated” (PDF: Demand model calibration report) to bring their predictions in line with known facts. Calibration can be manual, to account for failures in the model to come in line with observed data.

Weaknesses of the LSMATS modelling process

1. Junk in, junk out

The data used to calibrate the model is out of date and unrepresentative of the present scenario. The model’s developers looked at how many people needed to travel in 2011 (POWSCAR). They then split the figures by modal share, and then “recalibrated” the model by comparing it to observed data.

Bus passenger numbers were taken from June 2009, in the middle of a recession when DELL had just closed, overall bus numbers were down 5% in 2008 and a further 5% in 2009, and when the schools and universities were off. The June 2009 figures are referred to in Mid-West Regional Model – Public Transport Model Development Report (PDF).

The observed data for people walking and cycling was in November (2014), one of the darkest wettest months, and the locations measured exclude the high active modal share zone around UL.

The modelling process is therefore based upon inadequate and outdated observational data for multiple transport modes.

2. Manual calibration introduced car bias

The calibration process was used to bring the model in line with the outdated observational data, thus predicting a lower mode share for walking, cycling and public transport in 2040.

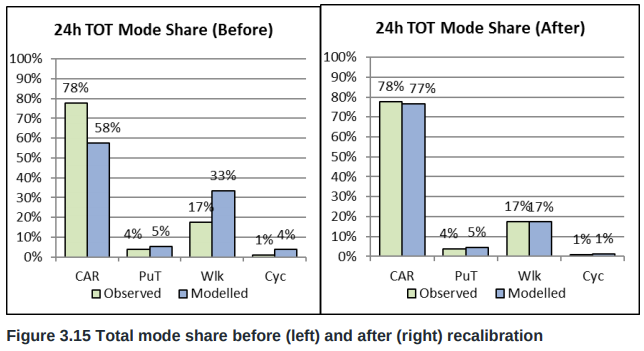

Page 43 of the calibration report (PDF) shows the effect of the calibration before and after:

In the case above, the attractiveness of trips by car has been increased from 58% to 77% in the manually calibrated model, due to the inadequacy of the observed data used.

Section 3.24.3 Recalibration of the calibration report describes the number of passes of calibration that were required:

“The first step in the recalibration process was to compare the modelled mode shares to observed data, segmented by user class and time period, in order to see how much recalibration was required. Following this, the ASC values for the 33 journey purposes were modified to adjust the relative cost of each mode so give a better match to the observed data. This was an iterative process which took seven passes to reach an acceptable level of calibration for the mode shares. An 8-loop full model run was done each time adjustments were made to the ASCs”

The divergence between the model’s predictions and observed data used to calibrate the model would indicate that the calibration process led to results that don’t adequately inform future real-world trends.

Additionally, it has been assumed in the LSMATS that a bus network is in addition to existing roads. The Limerick Cycling Campaign recommends instead international best practice whereby quality bus lanes must sometimes be used from existing road space, reducing the numbers of people who wish to drive, creating a virtuous circle.

3. Active modes not calibrated and found to be worse off in validation

The cost of walking and cycling should be “rigorously tested during demand model calibration” (page 17 of the active modes model specification report PDF).

However, page 60 of the calibration report (PDF) states:

4.7 Active Mode calibration and validation

As there was no count data available with which to calibrate the active modes network it has not been calibrated. However, the mode shares and trip length distributions do look plausible.

Active transport modes were therefore not calibrated.

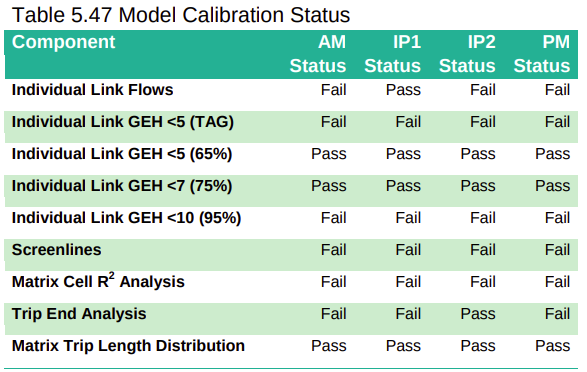

Further, page 72 of the MWRM Road Model Development Report (PDF) showed that the road model calibration failed to meet most of the calibration and validation standards:

4. Cycling mode share modelled on unrealistically low cycling speed

The model has underestimated the speed (thus attractiveness) of urban cycling. The modelling process includes the concept of “attractiveness” of transport modes in terms of how long it takes to go on journeys using different modes of mobility. Cycling “attractiveness” has been minimised in the modelling process, resulting in reduced predicted numbers of people cycling.

The Strava mobility app has recorded an average cycling speed of 22.5km/h in London. Yet, LSMATS modelled cycling speeds at 12 km/h due to the lack of quality cycle routes.

Other regions with quality cycle routes were modelled at 20 km/h. See Page 16 of the active modes model specification report (PDF).

Thousands of college students (up to 20 years old) have also been wrongly modelled to be travelling at the same cycling speed as infants (12*0.83 = 9.71km/h).

The modelling process should rather assume that quality cycle routes will be constructed to reach ambitious mode share targets.

5. Modelled northern distributor road capacity ignores multi-mode usage

The proposed northern distributor road “was modelled as a 80kph dual lane with grade separated junctions” (section 5.2.5, Transport Modelling Assessment Report PDF). This modelling over-accounts for the effects of such a road, as section 5.3.2 states, “It is assumed the LNDR will have a 60kph speed limit, single carriageway crosssection for cars, at grade signalised junction and bus priority, walking and cycling provision.”

Thus, the model has accounted for a faster higher-capacity road than a multi-modal road, adding a bias to the predicted number of car journeys made on such a road.

6. Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) highlights the lack of innovative investment

Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) methodology has been developing over recent times, and essentially should now include a full societal/health/cost assessment approach. The Strategy does include the recommended use of WHO Health Economic Assessment Tool for walking and cycling (see Appraisal Tools), yet travel time savings have been given a higher value in the modelling process.

In relation to cost benefit, a rate of return of 2.8:1 has been calculated in The Strategy with a discount rate of 4% (see Transport Modelling Assessment Report, pg 71 PDF). A 5% discount rate is standard, and has been used in Cork’s transport strategy. Choosing a 4% rather than 5% rate of return accounts for benefits too far into the future (many benefits accruing between 2070 and 2100, which is assuming the current infrastructure will even still exist then).

At a discount rate of 5%, the Strategy’s Cost to Benefits Ratio is only 1.7:1. Expected cost benefit ratio values of active transport projects are more normally in the range of 8:1 to 15:1.

Ultimately it is evident that the Draft Strategy does not provide adequate benefit relevant to its proposed cost, and so should be reevaluated for increasing benefits and reducing costs. The Strategy therefore lacks the just analysis of investments such as Bus Rapid Transit or tram lines.

7. Failure to model world-wide micro-mobility trends

A forward-facing long-term strategy should account for global behavioural trends. Micro-mobility technologies such as e-bikes, e-scooters and other personal mobility technologies will account for a growing portion of how people will get about in the future.

For example, Paris had 15,000 scooters available in 2019, and the EU Commission has been involved in exploring micro-mobility including a conference on micro-mobility services.

E-bikes are legal under Irish and EU law, and legal frameworks are imminent around micro-mobility technologies such as e-scooters.

The absence of accounting for this quickly growing trend results in the modelling process being already outdated, let alone providing a strategy for 2040.

Our Recommendations

- That the Minister for Communications, Climate Action and Environment and Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport immediately pause the consultation process and review LSMATS to overhaul it into a fresh strategy that provides ambitious and necessary targets for a transformed mobility strategy, and a viable, liveable future Limerick.

- The immediate funding and implementation of the proposed and agreed primary and secondary cycle networks as identified in the Limerick Metropolitan Cycle Network Study (Arup, 2015) and referenced in the Draft Strategy.

- Show a Cost Benefit Analysis of 40% car mode share, for example. That would provide economic prediction of whether Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) or tram lines would make sense in an overhauled strategy.

- As with the inclusion of a northern distributor road in the modelling process, also model the existence for a high quality cycle network.

Conclusion

LSMATS “outputs” of transport modal share for up to 2040 have been based upon weak input for the professional demand modelling that was carried out. The calculated benefits fall short, and thus miss out on innovative investment opportunities into the region’s transport networks.

Instead, transport modal share targets should be agreed in line with environmental, public health and local development policy and set as an overhauled strategy. A modelling process can then inform the strategy of what provisions would be required to meet those targets.